Denby Sheather on How to Live and Love in Death

Join Denby Sheather, author of the groundbreaking "Dying to Live: Learning to Live and Love in Death", for a transformative discussion that challenges our understanding of mortality and rebirth. In this insightful session, Denby explores the profound message that death is not an end, but a natural transition and a form of rebirth. She delves into various "types of death" we experience throughout life – from physical passing to ego death, the death of old beliefs, and even societal shifts – encouraging us to embrace these transformations as vital parts of being.

Transcript

Cate: So, welcome everybody. Thank you so much for joining us to have a bit of a yarn with Denby. Denby is an amazing writer. I think it's the third book in the line that you've written. Or is it the fourth?

Denby: It's about it's the fifth.

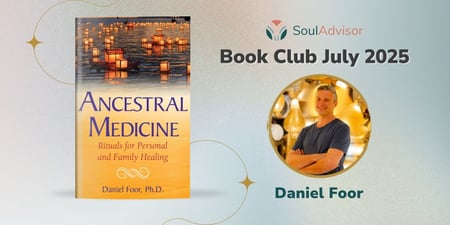

Cate: Oh, the fifth. My apologies. The fifth book. I didn't realize. Okay. Well, the fifth book. So, Denby is a very seasoned author and it's really exciting to be talking about a subject that we have quite a few authors focusing on. So we have Daniel for coming to talk about ancestral medicine, Hazel Volk coming to talk about the wisdom of the ancestors. And we also have—my brain has just gone, 61 years old—Joy Fairhall coming to talk about, she started with a book called "The Empty Pillow Beside Me" which is all about death too.

Before we start, I'd really love to welcome everybody here and acknowledge the country that I'm on, which is Yuin country. Ancestry and family of course is beyond important to First Nations here and across our country and throughout the world. And I know, Denby, that you've spent a lot of time in the company of people from community as well. And I just want to give deep reverence and thanks to the ancestors that are guiding all that we do in this context and hope that our sharing of knowledge with each other leads to a stronger community and more healing all the way through back through our lineages. So thank you so much, Denby, for joining us. Yay. And it's really lovely to have you here and welcome George who's just come on as well.

So, Denby, fifth book. That's an amazing thing. I just want to know how hard it was to come up with that title, "Dying to Live," because it's quite catchy.

The Genesis of "Dying to Live"

Denby: Well, I thought, and first of all, thank you, Cate, and everyone for joining and thank you for this opportunity, sweetie. I really appreciate it. It's—I mean, writing, it's—I always liken writing a book to childbirth. Like, for me anyway. Being pregnant and giving birth was the easy part. Raising the child is the hard part. Writing luckily has come easily for me, but the promotion and all like it's another job altogether to push it and to get it to where it needs to go and all those things. So any support is most welcome. So thank you, darling.

Yeah. Well, I thought I was very clever coming up with that title, of course, but then after I just—I chose it, I Googled it and there are plenty of other books called "Dying to Live." So it's obviously a very common title, which is totally fine anyway. It started off as a journal for me personally just to know, get out my emotions when we found out that my dad was diagnosed with cancer. So and at quite a bad stage, and so I just started blurting that out and realized through my own menopause journey as well that there was a lot of—like I was in, I was in the cauldron basically with a lot of different things happening at the same time in my life. And as a death doula, a death walker, a psychopomp, whatever word you want to put there, I've been doing shamanic work for quite a few years as well. And I've always been intrigued about death as the Greeks believe it, and I was born in Greece as well, that your birthday is actually your death day and the day that you die is actually your birthday. You return back to source or your infinite consciousness, to that expression of oneness, of infinite, whatever you want to put there. So that—and that really resonates for me.

So, "Dying to Live" is kind of an interesting way of suggesting maybe subliminally that, you know, you're leaving this physical body, but there's so much more potential and so much more out there to be experienced. I don't think any of us have really kind of got the idea of, I certainly don't, of what's actually going to happen when we go. We've got lots of fantastic histories, of course, and near-death experiences and our own ideas and intuitive hits on what happens on the other side. But yeah, I think we're pretty much up in the air as far as the afterlife. And a lot of people even believe that we've died. I heard this the other day. It's fascinating that we've actually already died here. And what we're experiencing now is that we've forgotten that we've already died and we're reliving everything to go back to, you know, another state of again, union with ourselves. So you could write a whole series of books on this one topic, I'm sure. And there are many amazing books. Steven Jenkinson, for example, comes out as a standout who works with the ancestral medicines as well. So, yeah, that's basically how I just chose that and learning to live and love in death—the subtitle—really coming to grips with, you know, losing my dad. I haven't lost a parent yet, and I'm sure that people listening and watching and here tonight that may have already gone through that rite of passage. So I'm not looking forward to that. But I also feel it's like because of who I am and the work that I've done for so many years, I'm quite prepared on that level. And I and I'm not seeing it as obviously a devastating loss, but because I know and I feel and I have these connections to what's on the other side. I don't feel scared about it as a lot of people do.

Cate: I think you're around death. I think that, you know, it's a beautiful thing that you say you don't feel scared. And I really like, you know, we need to change the way that we talk about death. It really needs to change. That message comes through again and again throughout your book. And, you know, it seems to me that death can be a real fear-mongerer. You know, like it's used as a weapon almost by those who wish to see people be scared. So, you know, "This many people died from such and such today," etc. So it's a—we really do need to change how we talk about death because, you know, I think what are the figures? I've done my end-of-life doula training. It's a bit, you know, it's a bit sketchy for me, but I think something like 68% of people want to die at home and only 12% do. So, you know, it's—we need to be prepared to think about it to make a lot of positive choices. And I just wanted to send an accolade to your dad who's done the forward in this book, which is fantastic given that it's all about his imminent departure from this planet. He finishes off with, "Enjoy the read, bye-bye and love to you all." I just think it's so accepting of where he's at. It's really lovely.

Denby: Yeah, that's, that's so my dad. He's, I mean, he's an academic. He's—to his credit, he's put up with a lot of the information that I have saturated with him or him with in the last two years since his diagnosis, and even before that, the last couple of years of what I talk about and have been—he's really opened his mind and he did have a double bypass a few years ago. And in my experience, people who usually have heart surgery that opens them up into that higher heart space, so they do tend to become a lot more receptive and compassionate and emotional. And I've watched—not that he wasn't compassionate before, he was—but I've watched him just feel safer to go into that part of himself as he's gotten older, which I don't think we see with a lot of older people. They tend to get stuck in their rut. And I, you know, I'm getting older, too, and I recognize that in myself. But, yeah, we wrote this together. And because being he's a professor, and he's all about speaking and writing, I he helped me edit it. And when I had the idea to write about it, I of course got his permission to share his story and everything. And when we did the opening down here in Avalon at Bocuccino, he came with me and he sat down and he gave a little speech and it was really lovely for him to do that. It's like one of the few last things that he'll get to do, you know, before he goes whenever that is. And especially as a professor who's spoken to thousands and thousands of people for his entire life. That was just a really special moment. So, yeah, he's just like that. He's like, "Yep." And he wanted to help with the eulogy as well because he's a Virgo and he's like, "Well, I want to make sure you get it right, that you don't miss anything out."

Cate: Yeah. In there with his boots on. And was it him or you that chose this beautiful picture for the front of your book?

Denby: Yeah, that was me. I found that on Canva, I think, actually. I was looking for something that was that sort of reiterated regeneration and that death is not the ending, that the death is the rebirth thing. And then I stumbled across that image and I was—that's just perfect, really, I felt. And I've had a lot of feedback on that as well. So I've—I've gone to change the cover a few times to make it look a bit fancier. You know book covers, you've got to have a, you know, that's apparently a big sell for most people. But I think, and you know me, Cate, as well. I'm usually pretty very simple and clean cut with things like that. So yeah, I think it speaks for itself with that and I when I showed him that, he got it straight away. He understood the symbolism of it.

Cate: I think it speaks to my heart looking at that picture very strongly. We're really pushing the agenda or pushing the idea that the heart is intelligent over here at SoulAdvisor. Wholeness, heart, healing, all of those words have a very similar root. And the—we're kicking off the global healing hub on the 25th of July with a beautiful movie called "The Heart Revolution." So I hope you can make that because you've talked quite a bit about heart just then and your dad's dad going through all of that and the intelligence that comes when the focus starts to shift towards the heart away from the brain. So thank you. Thank you. Thank you. And tell me so many chapters. I can see how your dad got inundated. How many chapters is it? I think it's something incredible.

Exploring the Many Facets of Death

Denby: Oh gosh, I don't even know. Let's have a look. I mean I've just got the draft here, but it's—yeah, as I said, it started off as a journal. There are 34. Well, 33 really, because the last one's "Farewell Dad," which is just a bit of a poem for him. It started off as a journal and then as a way of venting my emotions and all the stress that we were going through obviously. And then, I don't know, it just morphed into, "Right, okay, well, what are the other types of death that I've experienced in my life?" And things that a lot of people may not actually think about as a type of death or an ending, which as you know in the book, dementia for example. My mom's suffering from dementia and that's an end, it's a death of an aspect of the person, of course, as they move towards that. And often walking between both worlds as the veils get thinner and they start to see visions or they connect with loved ones on the other side or all that liminal space starts to happen. Menopause of course, you know, it's the big M. So it's a, it's a death of an aspect of the feminine as the next phase, you grow into the next one. So it's not an ending, it's just a transition. Ego death, I think we're all familiar with that one as well and I'm certainly still working with my ego as well. It's a non-stop journey.

I came up with the death of light. I interviewed a survivor of ritual satanic abuse many years ago and that just came to me of like the death of light, as I'm sure you guys are familiar. You've watched or listened to people who have been through severe abuse that there is that spark that goes, that's—there's a death of that person, the innocence of course. I went to remission as well. I've had cancer in the family before dad's situation and I'm a great—I'm a supporter of allopathic medicine but I also alternative, which is actually to me reversed because alternative was around before allopathic. So allopathic is actually the alternative. But remission is delayed death as I explained it in this book and I shared my experiences. So I started thinking, "Okay, well these things that I've had in my life that I've lived through." I talk about abortions that I've had and that's obviously death. I talk about stillbirth and invited some friends to share their stories. There's been murder in not in my family but through very close friends and I write about that. So all—once I started it was just like all these different things that came through. And of course, these things, the death that's happening with that, the death of truth, the death of sanity, common sense in the last six years especially. And then getting a bit more intense, the death of gender and all everything that goes with that and the death of death. The concept of like, what if we lose the ability to actually die? You said before, Cate, that we all have this ingrained fear of death. And that is definitely embedded in the human psyche. But what if we took that for granted? What if we couldn't die and then we were stuck in this hell loop, for example, as a consciousness, as a machine? All that sort of stuff came to me as well. So I just, I just opened it up, typed it out, got edited and published it and just went, "Cross my fingers," and went, "It'll, it'll reach the right people."

Cate: Well then, you're, you know, you are a very brave soul. You've always been a brave soul. You've always spoken to truth and spoken your truth and, you know, it was a fascinating book because having done my end-of-life doula training and being used to reading a lot of books about death, I started flickering and went, "Goodness me, this is wide-ranging." And I love that you've brought it to the fore that death is just as much a part of being as of being born, you know, born, dying, it's the whole shebang. So thank you very much for that. It was really fabulous.

I'm going to ask you to do a bit of a reading for us and then I'm going to invite conversation between everybody. And but could I make a request that you read that beautiful Indian poem that you've started off with to start with because it's such a beautiful poem and that and the continuity of, you know, beyond the veil, I would really love you to bring to the fore.

Denby: Of course. Yeah. And of course this is not mine. It's a Native American prayer.

Cate: That's the one you mean at the very front. That's the one. Yes.

Denby: Okay. Sure.

"I give you this one thought to keep.

I am with you still. I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow.

I am the diamond glints on snow.

I am the sunlight on ripened grain.

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning's hush,

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circled flight.

I am the soft stars that shine at night.

Do not think of me as gone.

I am with you still in each new dawn."

Just gives me shivers every time I read that.

Cate: It's so beautiful. Thank you so much. And, you know, I have that constant feeling that there are those with us who've passed on out of form, constantly. And, you know, and I think in that thought it keeps us all so much more honest and working as I do in First Nations down in Yuin country that's just understood down this way that, you know, everybody who's passed is listening on and hearing everything you think and say and do. And so is every tree and every bird and every rock. And so, you know, it keeps us connected and less likely to commit the kind of things that we wouldn't want to see happen to others. Yeah, it's a very beautiful, beautiful poem. Thank you. All right, over to you to choose.

Denby: Oh, you want me to read something else or not?

Cate: Yes, I'd love you to do a reading. Yeah.

Denby: Oh, running out. I hadn't even thought about that.

Cate: Oh, that's okay. The format for everybody else who's here is we've been doing 15 minute introduction and then a 15 minute read, but it doesn't have to be 15 minutes, Denby.

Denby: No, no. This is literally the last words. Oh god. And it's only short otherwise I don't want to drag things on. Okay. So I'll do that. And this is the last, the ending word, the ending chapter. And I started each chapter with a quote for those who haven't read it yet, that sort of, you know, leads you into the topic of each one. So this one's by Jimi Hendrix: "The story of life is quicker than the blink of an eye. The story of love is hello and goodbye and until we meet again." Which is beautiful.

"This is the final line of the poem Hendrix wrote on his deathbed. Apparently, profound to the end, or the beginning as we have explored. We have covered a lot in this book. So, well done for reaching the end. Thank you for persevering and keeping an open mind. It has surely given you food for thought and hopefully inspired you to start investigating the death and life portal more deeply for yourself. For those supporting family, friends, or themselves through the dying rites. Now, I send you love and prayers. For as you have discovered, you are not alone. Death doesn't discriminate. It comes for us all in due course. But there is no point in being afraid of that which you cannot control. Instead, see this as a blessed opportunity to take charge of your spirit and claim all that you are and always will be, for that is what you came here to do. Choose to use death as the instrument to restore your birthrights as the dawn, not the dark. A chance to set things light. I don't believe in the doctrines that insist our physical death will be followed with an eternal series of deaths in some realm of fire and brimstone if we insist on denying God. Some would say we are living hell here and now, and they may be right. Recent years can certainly be interpreted as torturous in many ways, but as retribution for centuries of sin and blasphemy. I'm not fully convinced. I don't believe a loving creator would punish us in such a way. We have become experts at torturing ourselves over time anyway. That much is obvious. If you take anything away from 'Dying to Live,' let it be the courage to keep exfoliating the layers of ego and fear that no longer serve you and cultivating the trust to allow your body, nervous system, heart, mind, and spirit to come back into full being and balance. May we all learn to live and love in death. Blessings to you and yours."

Cate: Oh, beautiful, beautiful, beautiful. I'd love to encourage everyone to jump in and share their thoughts about death or where they're at on the death journey and ask Denby questions about everything that she's written. You're such a gifted writer and I'm so glad you've written five books. Now I have to go and read the other four.

Denby: You're welcome. Thank you. Yeah.

Personal Experiences and Cultural Perspectives on Death

Cate: But, you know, I would love, love, love anybody who might have a question for Denby or to share where they are in their thinking about death to hop into the conversation, please. Oh, George has unmuted himself. Is that a yes?

George: Yeah, I've just got a bit of background noise happening. That's right. This is again a personal thing for me too because on Monday it will be my mom's first year death anniversary. So we lost my mom last year and in fact I lost my stepdad and my mom within four weeks of each other.

Denby: Wow.

George: And I had never been with someone who passed. So, I was fortunate to be with both of them who passed away and not knowing what to expect and then actually experiencing it. And they were both very similar in that passing component. My mom was a little bit more, she had a respiratory infection that put her away, but my stepdad had a prostate bladder infection, a bladder cancer, and he just pretty much bled into his bladder and passed away. But in Chinese medicine, we talk about the spirit or the shen and that the shen is represented through the brightness of the eyes. And we were, I was with my stepdad. He was the one who passed away first. And the nurses were there just changing him. It was early morning about 7:00 and he was going to—that was just going to lift up his bottom to pull the things out and then his eyes fixated and I'm looking at him. So, "Where's—what's he looking at?" And it was like right at that point in time, the nurse knew actually what happened, but there was like no one home. The spirit had gone, but he was still breathing. There was still that breathing component and it was actually quite smooth. It was like a wind down, whereas he had a mask on to begin with because he had respiratory issues and they took the mask off to change his top and he's gone into—put the mask back on and back to normal. But when that shen left, it was like there was nothing there and they took the mask off and it was just a slow rhythmic and then it had just eventually stopped. And it felt like it took about a minute or two for that process to occur. And exactly the same thing with my mom. I was holding her hand and again it's like her eyes just dull, nothing there, but she was still breathing. But because she had fluid on her lung, it was again smooth, but it was short-lived. So it was quite—Yes. Now it's, it's like once that once that shen disappears the fear of not being able to breathe because as a young kid I had lots of asthma and I choked once and I remember running trying to get your breath and that fear that I had then has now been cleared because I've seen it twice happen where it was just such a peaceful ending. And I think it can be even more peaceful just comparing my mom to my stepdad if you're already in that state of connection to the to that sense of what you were talking about before, Denby, to that connection of the universal energy or the the mahat or whatever one would like to call it. So yeah.

Denby: Yeah, totally, totally, George. Yeah, thank you for sharing that and I'm sorry for your loss. That's, that's hardcore. I have, I have an intuitive sense that when my folks go, they've been together for like almost 60 years, that they're going to go very closely together as well because they literally couldn't survive without one another. Yes. You know, it's probably a good thing. It's a good thing for them because it would be awful to have one pining for the other, but it's going to be pretty intense. So, I can empathize with you there. And as Cate would know and anyone else who's done any death doula training and end-of-life end of care—I mean a lot of people don't like the word death, I just say death end of end of life care or whatever—it is a very beautiful peaceful space ideally and naturally, but of course with a lot of things that have been medicalized and certainly birth, and Cate, you relate to this as well, and certainly your land will that it's been medicalized and it's been organized and and taken over and fractured as well. So, it's—yeah, we we've been programmed or conditioned to anticipate that these things, whether it's childbirth or, you know, going into labor or death, are going to be horrendous for everybody. And yes, of course, sometimes that is a lot of the case that is depending on the circumstances obviously. But how beautiful that you got to see that because in my experience with clients and also myself and my family and losing—I lost my nephew to cancer when he was five, probably about 25 years ago now. Being at home with him as he took his last breaths, that was very, I mean, that was the making of me as a shamanic practitioner. It just changed everything in my life, especially now, goosebumps now thinking about it. And I write about him in the book, of course, as well. He's, he's always—he's right here now. It's—it's just such, it's, it's a beautiful space. And again, once you allow the fear—the opposite of fear as we all know is love. You allow yourself to drop into that space and you have some sort of connection doesn't have to be perfect or right about your sovereign soul and where you choose to go back to or where you'd like to and where you'd like to navigate to. That creates a lot of healing not just for the person observing, I mean, sorry, dying, leaving, but for the family as well, of course. So it can heal a lineage in many ways as we say, seven generations forward and seven generations back depending on how conscious somebody is at the time, of course. Not as conscious as in the sleep, but you know, awake, aware, whatever. So it's—and in hospitals, not the ideal. Sorry, my son's just texted me to pick him up from work. I'll turn that off. My folks want to die at home, because they've lived in this and my grandfather died in this house and that's their plan. And so, we're doing everything to try and make that happen. But at the same time, I'm also preparing them, because if something happens and they go into fear, they're probably going to reach to, you know, some sort of external support or an authority like that and they may end up in hospital in their last hours. And you know, I've got lots of friends who are nurses who have been through that experience many times obviously that are very good and they're all, you know, I've got them on speed dial if that does happen. But ideally, I'd like to see them just and I would like to, I just like to go to sleep and just not wake up or have all my family around me as I—my first death I ever experienced was my beautiful grandmother who died and we were all there holding her hands. And we just watched her as you said, George, that breath just going and it's a bit of a death rattle and it can sound a bit scary sometimes and you hold your breath with them and then relaxes and everyone's like, "Is that the last one?" And, you know, it's, it can be very unifying and healing for the family if they're open to go into that very sensitive space in their heart as you say with the shen. It's, it's all about the soul and the spirit and our willingness to be in that raw, vulnerable, intense, compassionate, everything space in ourselves. And I think as humans we've been conditioned to not go into that space. That's another conversation altogether.

Cate: Yeah, it's interesting. I was listening to someone and they were making the comment that when we go to sleep, we're actually practicing death because where do you go? Yep. So, we don't think about it in that particular way, but we're going into that space of wherever that is with the brain wave slowing all the way down and yep, we wake again. So provided that the sun and the planet Earth is within its same going around and, you know, maintaining its whatever we want to call it, its space within space, then everyone's going to be okay.

Denby: Yeah. And I think, George, you coming from your background, the microcosm and the macrocosm, you know, sleep is a little microcosm of the eventual letting go and hopefully the waking up somewhere. Yes. Whatever. Yes. Who, who knows where we go to, but who knows? Yeah. And that, those are the two magic words, Cate. Letting go. Just letting go of your, you know, your attachments, your fears, what your expectations, your identity, all these things that, you know, have taken all of us as we get older certainly come to a, you know, a more honest relationship with ourselves with those things. I think I'm quite different in with these perspectives as I was when I was in my 20s and 30s obviously now, but yeah, it's, it's the surrendering into what is going to happen. And again, worrying about something that we don't know. I mean, if you want to go into astrology and all those sorts of things, there are people that say that's all mapped out before you get here and it may well be. But worrying about things in case they might happen, I don't necessarily, you know, follow the teaching of like if you think something bad is going to happen to you. But if you know, that's why the "Dying to Live" is interesting because a lot of people do actually get busy dying without even actually living their life and they live in they, they waste so much of their time and their life and all beautiful opportunities and relationships and things like that because they're holding so tight to either an identity or something they wish would happen or hadn't happened etc. So there are so many different layers. I might do a, you know, I'm sure that I probably will. I don't know when, whenever it is, when I'm ready. When my parents do pass, I'll do a sequel to this. But I'm not putting any energy into that just now. I'm caring, I'm helping to care for them and just working through that. And that's exacerbating and amazing and frustrating and everything all at once. But it's a real privilege at the same time to be here with them as they age. And, you know, giving back is the ultimate service, isn't it, Cate? In yoga, looking after your parents when they looked after you.

Cate: Absolutely. And I think, you know, you're surrounded by therapists here at Denby of different sorts. We're all in service. Yeah. Would anybody else like to ask Denby anything or add any comment?

George: Yep. I've got a question actually for Nuth if that's all right. What's the—yeah. What's the Cambodian ritual or perspective culturally around death that you've that you've learned or been prepared for or experienced?

Nuth: Over here, when the elders, when their family knows that they're preparing to go. It's what, yeah, it's what they say here. So they will have the monks from the pagoda give out blessings and praise and, yeah, everyone just gets together, all the family members, they all come together and just be there before, before they pass. And, yeah, I think it's quite a beautiful process. And I also got to experience that with my grandmother as well. I think she has passed for almost two years now. Yeah. Everyone just, it's, it's a time for everyone to just say their final goodbyes to the person passing.

Denby: Yeah, that's beautiful. It sounds like it's almost, and I suggested this to dad as well. I watched a movie, I can't remember the name of it, where the lady is dying of cancer and she wants to have her wake while she's alive. I don't know if anyone's seen that. And it's the most beautiful movie. It's done so brilliantly and it's funny and it's sad and you're bawling your eyes out and laughing. And I said to dad, "Do you want to do that? Do you want to have a, you know, a wake with everyone together? So, you know, while you're there, you can say your final goodbyes." And he sort of entertained it for a while and then we just sort of, no, we didn't go any further with it. But it sounds like it's kind of like that, which I find—I think that's beautiful. It's a really lovely connection, especially when you think that most families maybe not even then get together once a year for Christmas and that's about it. It's a really sort of a good way to get to inspire families and communities to stay more connected. So, and the fact that the monks come in and there's such a beautiful—I mean this is the thing with a lot of white Western culture is that we've just lost so much. We've just lost touch. We don't have men's business, women's business. Our children aren't taught that. It's got a lot to do with all of our phobias and violence in society and things like that and our approach to death and the respect or the lack of respect for those things. So yeah, it's interesting to watch a lot of different indigenous cultures around the world still, like that poem I read, still have that beautiful connection to the spirit. It's all about the spirit first and then the body second. Whereas we tend to focus on the body and making sure that everyone stays alive to the last moment because that's proof of, you know, success and whatever. And a lot of the time the spiritual side, the spirit aspect of the person is dismissed or sometimes even ignored altogether. So yeah, thanks for sharing that. It's interesting.

Martine: I just had a beautiful experience when my mom passed away a few years ago. She was losing weight and deteriorating. She was not in pain or anything. It was quite peaceful, but I didn't want to focus on her body. So I tuned in and I asked to connect with her spirit and that was just a day before she passed. What I saw was like a huge wax candle, very low. The candle had melted almost to the bottom and the flame was huge. The flame was like ready to take off. It looked like a rocket. And when she passed away the next day, I tuned in again and this time it was a round sun, brilliant sun hovering over her body, just ready to finally go. It was beautiful. So yeah. One of my patients said to me, you know, spiritual beings are there at your birth and they are there at your moment of parting. Because she saw that when she had a child, she could see all the people in white in the room and nobody could see them. But then when her father died, she also saw all these beings of light. So she knew he was very close. So, we're not alone when we die.

Denby: No, not at all. And that reminds me, you might hear my dog snoring in the background there, but when my staffy, my other staffy, died probably about nine or 10 years ago, we were burying him in the garden here, just as a side tangent, sorry. We just put him in the earth and I was crying my eyes out, of course. My son was seven, I think, his first experience of death. And he nudged me. He said, "Mom, look, Buddha's up in the tree." He saw his spirit sitting up in the tree watching us bury his body. So this happened—I've had that—I got goosebumps again. I've had that with my other dogs as well as my horse. I've had a beautiful experience I write about in the book too. So yeah, there's so much more between heaven and earth than meets the eye, that saying. It's a scary topic to talk about but you know we can't avoid it. So I think the more that we do have gentle, open and conscious conversations like these and these opportunities and share our experiences with each other then it just helps to sort of nudge us a little bit closer back to those traditional beautiful cultural values and practices which is all about, you know, you said shen, George, all about the heart, about that toroidal field that we all share and that we're all partly responsible for nurturing.

The Positive Aspect of Death and Healing

Cate: Absolutely, Denby. Really. And, you know, what I've loved about just talking with you these last few minutes is the positiveness of death and the healing that comes from a death done well. Nobody has shared, you know, of course it's hard. It's hard to be born. It's hard to die. They're not easy passages, but they give so much, don't they? And if we can harness and be back in touch with that opportunity to grow and to come together as community and family and lineage then that would be a great thing. So we'll just keep focusing on death over here at Soul Advisor. We have done quite a bit of it anyway and talking about it as being a really, really important part of the equation in holistic health. Like death helps us to live, which is why I just love your love your title, "Dying to Live." And I want to give deep thanks. Is there anything else you'd like to say before we finish up?

A Story of Acceptance and Transformation

Denby: Just on that note when you were saying that, Cate, I've just finished with one of the more recent clients that I've had who passed from cancer. He was talking about people's—He was 43 I think. Being willing to change views and perspectives and start eating better and doing meditation, all these things. He literally turned his life around initially because he wanted to and he did know blood transfusions, the whole gamut, like just threw everything at this and did all these new techniques and went to America and did all these amazing things and did that for quite a while. I was seeing him on and off as a client during that time and supporting whatever he wanted to do, which was, and I learned a lot through that too. And then he did reach a point where it was—and I knew that he would—but as you know, it's never your point to tell a client anything. But I knew that we would reach this point at some point. And when we did, it was beautiful to see him just rest into that acceptance of, "I've done everything that I can." Standing right next to me now. He'd made peace with his family and he had trained in all sorts of amazing meditation techniques and he just got himself so in the zone. It was beautiful to watch and it was such a privilege to be a part of.

When he was passing, he just lives locally around from me and his wife rang me and said, "He's on his way," and I said, "Well, you know, he's asking for you," which was such a privilege. So I dashed over and sat by the bed and I just said, "You know what to do, mate. You've got it. We've been doing all that." And he's like, "Yep, I'm ready. I'm good. I'm ready to go." And I literally walked out the door and then he passed with his family holding his hands, like literally 5 minutes afterwards. It was just—that was so inspiring. And such a beautiful story. As I said, with children that pass early, as a parent, no one ever wants to lose a child. Of course, it's horrendous regardless of the circumstances, whether it's cancer, an accident, something else. But to see someone who had just literally just flipped their life values and everything on its head and just opened up, I like to think that wherever he is now that he's just—he's just elevated his next reincarnation loop tenfold, 100,000-fold. But, yeah, so there's always, there's always something new to learn in all of these things, which is my point, I suppose. But yeah, I just wanted to share that. And thank you everybody for turning up and for listening to me and hopefully you will read the book and it will serve you well.

Cate: And thank you so much, Denby, for giving so openheartedly. Thank you everybody for joining us on this cold wintry night. And please do share this amongst your friends. We'll let you all know when we've topped and tailed and edited. And thank you. Thank you. Really appreciate it.

Denby: Thank you, darling. Thank you, everybody. Blessings to everyone.